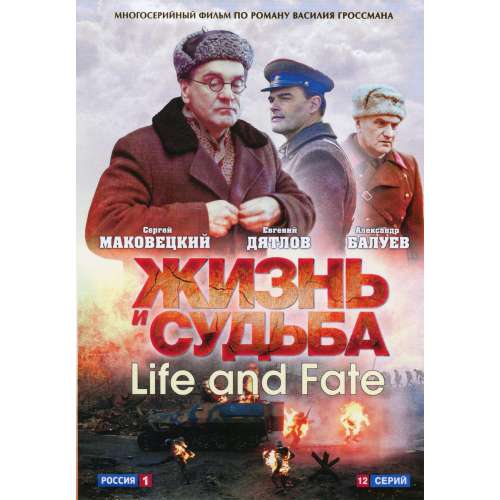

The blurb for The People Immortal says that the book is “far from being mere morale-boosting propaganda”. This new translation restores many of his lines that the Soviet authorities removed How can I shape my dumplings properly?” Soviet civilians are there too: the heart of the people is represented by a Cherednichenko’s young son Lionya, and his grandmother Maria, whose efforts to flee their apartment add human drama and underscore the theme of the importance of a secure homeland. Among others we meet Bogariov, a former professor now charged with leading this “important mission” Ivanovich, an expert in military strategy impatient with those who aren’t the calm, reassuring senior officer Cherednichenko and in the lower ranks, soldiers Ignatiev, Sedov and Rodimtsev.Īs we might expect, there is a good deal of vivid action writing, such as a virtuosic account of the “death of a city” by German bombing: “There was something indescribably painful about these few seconds, when many tons of death had been released from the planes and had not yet touched the earth.” But Grossman humanises his tale with occasional comic touches: the army top brass argues about the ripeness of the apples supplied to them, while their cook complains about “all this damn dive-bombing. The narrative drive comes from the Russian attempts to retreat safely – victory is simply getting out of the German encirclement alive – and the story is told largely from the viewpoint of the army. The story is based on an account given to Grossman by a Soviet officer of how he led a Red Army unit out of German encirclement after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. From 1941 Grossman was a reporter on the army newspaper Red Star, and this novel draws on his experiences and contacts there. Now we are reintroduced to Grossman’s 1942 novel The People Immortal in a new expanded translation by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. These books are not of the same calibre as Life and Fate: even on its first English publication, Grossman’s early novel Stalingrad was called a “ socialist realist dog” and a “ gelded fictional brontosaurus”. The Soviet writer Vasily Grossman already had many of his books available in English at the time of his death in 1964, but a renewed surge of interest in his masterpiece Life and Fate over the past decade means his other work is being rediscovered. S ome authors have a very active afterlife, though the results when the writer’s literary estate dips its hand in the bran tub marked “other works” can be very mixed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)